Summary

- Price developments are currently settling across the basket at large. This is happening throughout the G20 countries and is reflected in central bank activity.

- A strong correlation between real interest rate differentials and the weak euro persists at present. This is primarily induced by a hesitant ECB by global standards. Even a first timid interest rate step of 25 basis points does little to change this tendency.

- If the ECB does not adjust demand to the reduced supply in a more committed manner, inflationary tendencies and a weak euro can be expected to continue. An appreciation based on interest rate hikes could counteract both.

- Analogous to the euro, the yen depreciated strongly in the course of the year. This goes hand in hand with the widening interest rate differential and the continued ultra-loose monetary policy in Japan.

- The fluctuations in demand in China triggered by lockdowns led to very volatile commodity markets. As a result, the closely linked Australian dollar experienced strong appreciation trends in the first half of the year, followed by corresponding depreciation movements. Should the Chinese economy sustainably overcome the Covid lockdowns, appreciations of the AUD, but also of other commodity-sensitive currencies, are to be expected.

In the last FX market report, we identified three main drivers currently influencing FX markets. These were inflation dynamics and a resulting new interest rate cycle, strong safe-haven flows, and a tight commodity market induced by a mix of Ukraine war (supply shock) and Covid aftermath (demand shock). The majority of these factors have led to a structurally weaker euro against a broad basket of different currency pairs so far this year.

This quarterly report describes the advancing interest rate cycle, presents the consequences and then elaborates on the geographically heterogeneous effects. In particular, the relevance of the currently unstable Chinese economy for the currency market will be illustrated.

The interest rate cycle adjusts to price dynamics

The price level continues to rise globally, causing central banks all over the world to tighten their monetary policy. In the course of this, bond-buying programmes have been further scaled back (quantitative tightening) and in many countries key interest rates have been adjusted, which among other things serve to control aggregate demand. In the process, inflation is becoming more and more entrenched in the broad basket of goods. In Canada, for example, 70% of goods and services price increases in the representative basket of goods are already above the defined target corridor of 1-3%. In the Eurozone, this figure is now 75% (above a target of 2%). Other indicators also point to the fixing of inflation.

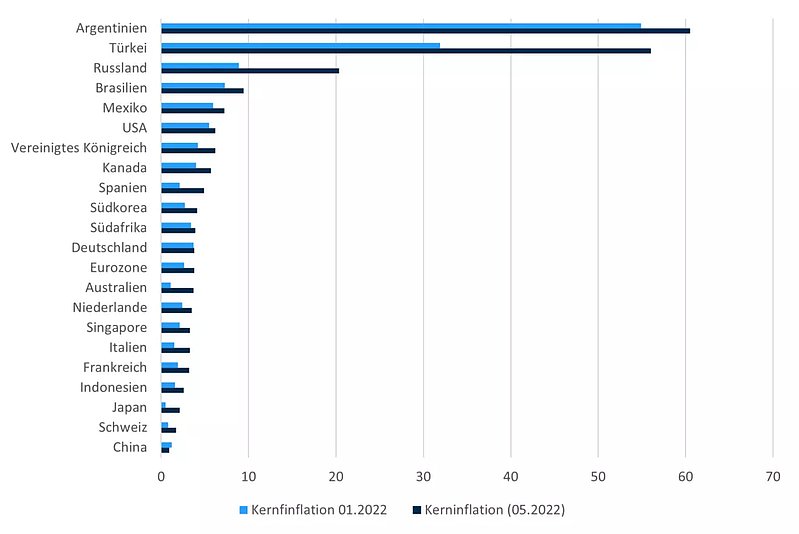

Compared to the beginning of the year, the core inflation rate has risen noticeably in all G20 countries (with the exception of China) (see Figure 1), which in turn has forced central banks to abandon their previous argumentation that price developments are mainly driven by energy.

Figure 1 | Core inflation - Current development compared to the beginning of the year in June or next possible date

Source: OECD, World Bank

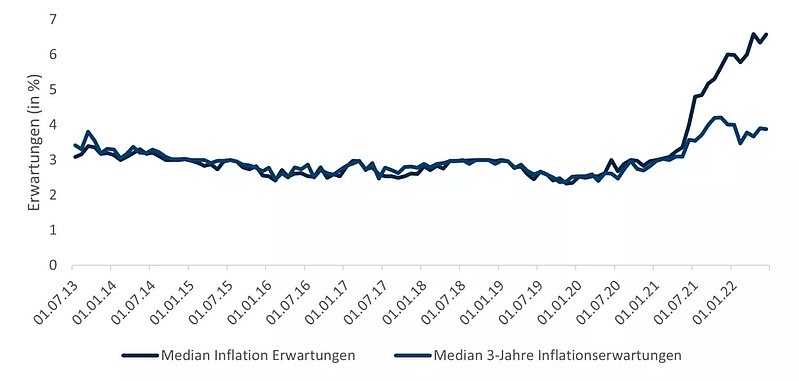

Another indication of a firming of inflation rates are the inflation expectations of market participants. The Federal Reserve New York published the median expectations for the coming year and the next 3 years (proxy for long-term expectations) as part of a broad-based consumer survey (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Consumer inflation expectations in percent (as of June 2022)

Source: FED New York

An adjustment of key interest rates is inevitable in this context, only the timing of the increase is controversial in some countries.

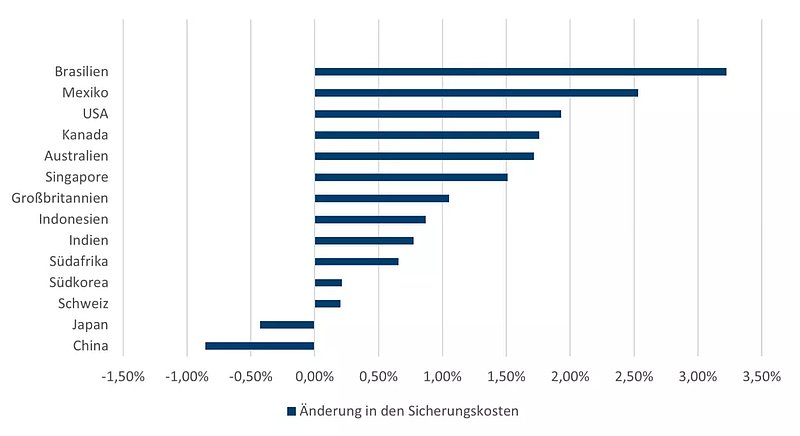

The different adjustment speeds of the central banks have dominated and continue to dominate the foreign exchange markets in this context. This dynamic is reflected both in the exchange rates and in the hedging costs (or returns). For a majority of the relevant economic areas, there have been significant expansions in hedging costs since the beginning of the year from the perspective of a European-based investor (cf. Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hedging cost expansion from a European perspective in percentage points (as of June 2022)

Source: Bloomberg

The US Fed is currently particularly aggressive in its monetary policy and has already adjusted the Fed Funds Rate three times in the course of the year in the corridor of 1.5% to 1.75%. Further rate adjustments are priced in and the Fed reserves the right to tighten further beyond that. At an emergency meeting, the ECB decided to develop a set of instruments explicitly designed to prevent a "fragmentation" of the Eurozone.

of the Eurozone. Translated, this means reinvesting the maturing paper from the PEPP (Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Program) bond-buying programme with a focus on the highly indebted euro member states. This debt spread targeting would partially counteract the planned European tightening of monetary policy, as refinancing costs would be synthetically lowered in some countries.

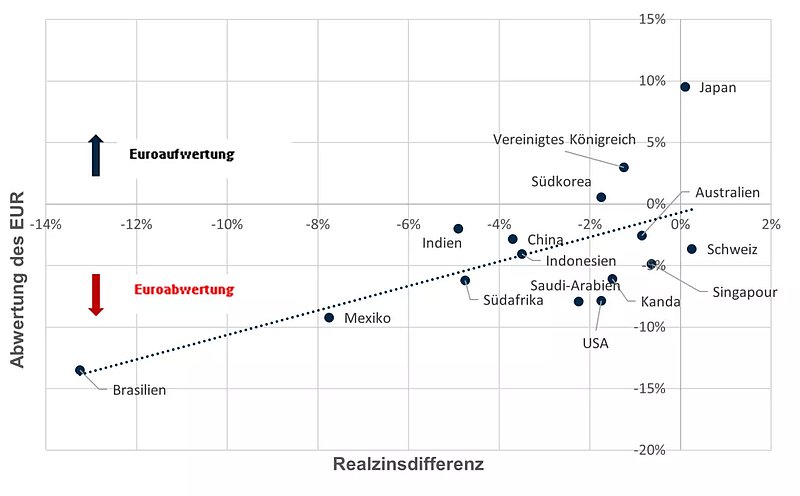

This, as well as the safe-haven flows resulting from the Ukraine war, led to a strong USD appreciation and a euro depreciation vis-à-vis a number of currencies. The following figure illustrates the depreciation tendencies of the EUR since the beginning of the year in relation to the inflation-adjusted key interest rate - the real interest rate.

Figure 4 | Depreciation of the euro against a number of G20 currencies since the beginning of the year.

Source: 7orca Asset Management AG, Bloomberg - (June 2022 or the latest available data point)

This illustrates a macroeconomic relationship. If a rising price level, ceteris paribus, is not responded to with an increased policy rate, a currency depreciates. Even if this is a simplified and rather descriptive view, since other factors also have an impact on exchange rate developments, this is very relevant from the perspective of many market participants and has a clear effect via this psychological component alone.

The problem that arises from this is that devaluations, as in the case of the euro, have a reinforcing effect on further price developments. The devaluation of a currency induces an increase in the price of imports, especially of raw materials (mostly paid in USD), which currently have a particularly price-driving effect. In April 2022, the German Institute for Economic Research published a study showing the statistical significance of this correlation. According to this, an interest rate increase that pushes up the yield of the one-year federal bond by 25 basis points leads to a price reduction of heating and fuel in the amount of 2-4%. Thus, central banks can have an influence on inflation, even if it is primarily supply-side.

The dynamic results from a structural imbalance between supply and demand and could historically always be broken with an adequate adjustment of the key interest rate. The longer price developments remain above a stable level, the more difficult it becomes to reset it to such a level, as the price level becomes fixed in the expectations of market participants in particular and this perception would have to be actively broken.

In Japan, the dynamics are analogous to those of the Eurozone, albeit at a different level. The Bank of Japan continues to emphasise that it will not deviate from loose monetary policy and is currently only considering a weaker form of yield curve control in the most offensive scenario, in which control only takes place on the short to medium end of the yield curve (up to 5 years). Consequently, the JPY depreciated massively on the basis of this monetary decision and the outlook. At its low point, it lost about 13% of its value against the already rather weak euro. In contrast to the Eurozone, however, a certain price increase is desired here after decades of deflationary tendencies. However, this is currently taking place at a much lower level than in the Western world. The reasons for this lie in the high price sensitivity of the Japanese, as a result of which price increases are absorbed to a considerable extent in the profit margins of companies. But other reasons, some of which seem paradoxical, also play a role. The diet, for example, is fundamentally different from that of the European world. Dietary habits (less wheat, more rice) partly saved the Asian world from the consequences of the Ukraine war.

The second metric that is highly relevant in central banks' interest rate decisions is the economic activity of an economy. Since many countries tried to insulate their citizens from the shock during the Covid pandemic with Keynesian, demand-stimulating fiscal measures, increased demand met reduced supply. This is now being unloaded in the present price pressure.

This is particularly evident in the example of the GBP. Paradoxically, high economic growth figures (8.7% in March) and low unemployment (3.7% in March) are not necessarily a reason to rejoice, as they are symptomatic of the phenomenon described and speak for an "overheating" of the economy. The Bank of England is already warning of recessionary tendencies in the coming year for this reason. This explains, among other things, the present weakness of the British currency.

On the basis of these observations, the following economic causality emerges: the more generous the Covid aid, the greater the excess demand, the more serious the inflation problem and the sooner the pressure to adjust key interest rates. If this is not done, the more likely it is that devaluation tendencies will manifest themselves for the GBP, which in turn will have a reinforcing effect on the price level.

Geographically specific factors - commodities and China's role

In addition to price and interest rate developments, there are a number of other factors driving the exchange rate, which, however, have different effects in different economic areas. In particular, higher commodity prices affect the exchange rates of energy and commodity-exporting countries. A high trade surplus supported the currencies of Canada, Norway and Australia in the first half of the year, as this was accompanied by excess demand in the real economy.

In Russia, the rouble appreciated more significantly after an initial sharp depreciation. In addition to the capital controls introduced, a record trade surplus had an effect, which was driven on the one hand by a slump in Western imports and on the other hand by an increase in the value of exports. The latter is mainly due to the price increase on the commodity markets.

The commodity-driven appreciation pressure eased in the meantime, largely driven by Chinese demand. No market illustrates China's rise in recent decades more clearly than the commodity market. China now imports about 75% of the iron ore traded globally. The 60% of global trade volume provided by Australia is almost entirely accounted for by China (source: Statista (Import Value of Iron Ore to China, 12.2021).

Experts often cite as a rule of thumb that almost every natural resource is consumed by 50% or more in China. Be it copper, aluminium, steel or coal, China dominates as a consumer. This is due in particular to the fact that China traditionally manages its set economic growth quotas through infrastructure programmes. These are inherently resource-intensive and the high demand for construction steel in particular regularly stimulates iron ore demand.

This high interdependence between Australia's trade surplus and Chinese demand caused the AUD to fluctuate sharply. At the beginning of the year, the AUD initially appreciated on the back of robust Chinese demand and supply deficits resulting from the Ukraine war. When lockdowns were enforced in China on the basis of high infection figures, ports were closed and the construction industry was affected, this had the opposite effect on the AUD. However, it can be anticipated that when the Chinese economy opens up, catch-up effects will kick in to achieve growth targets and thus a stronger appreciation of the AUD could set in.

For China, the recent series of lockdowns in important metropolitan regions had a substantial impact. This applies to macroeconomic performance and is also reflected in the CNY peg to the USD. The former is reflected in very weak fundamentals. On the price side, core inflation dynamics relative to the consumer price index (see Figure 1) actually declined (0.9% versus 2.1%). However, this is indicative of the markedly curbed demand, which has a dampening effect on both prices and the real economy. At the same time, industrial production contracted by 7% month-on-month, unemployment rose to more than 6% and the balance of payments shows the largest deficit since the financial crisis in 2008 (source: tradingeconomics 05.2022).

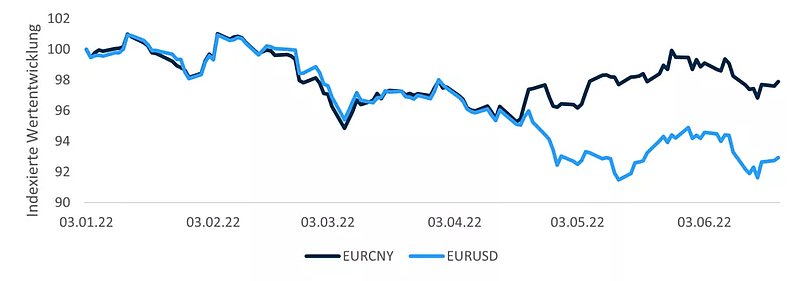

Due to this exceptional situation, the CNY decoupled from the USD (cf. Figure 5.). This is due to the fact that the capital outflows from China were at times so massive that even central bank interventions could not save the CNY exchange rate from the significant downward trend.

Figure 5 | Decoupling of the CNY from the USD since the beginning of the year

Source: 7orca Asset Management AG, Bloomberg

Geopolitical tensions have also had an impact on other economic areas that are more peripheral from a European perspective. The Chilean peso has appreciated significantly against the euro since the beginning of the year. The reasons were the robust copper demand and the supply deficit caused by Russia in the course of the year. In recent weeks, it has lost momentum due to falling Chinese demand.

In general, (commodity-exporting) developing countries are currently facing two sets of problems that subsume some of the key points of this report:

- Highly volatile exchange rates can lead to declining foreign currency holdings in a falling market. Managing foreign currency reserves is an important means of central bank intervention and is intended to support the domestic economy.

- Countries whose currencies are pegged to the USD are keen to maintain a positive interest rate differential with the US in order to avoid a spiral of devaluation tendencies, capital flight and central bank intervention. Therefore, an offensive monetary policy is currently to be expected in these developing countries. If the ECB does not sufficiently support the weak EUR, it will also depreciate against many emerging market currencies.